In the January 1998 issue, Popular Mechanics boarded the U.S. Navy's newest (and deadliest) attack submarine, the USS Seawolf. After the Cold War, the U.S. pivoted away from these heavily armed behemoths of the deep, but the Navy's upcoming submarine, currently named the SSN(X), could be as armed to the teeth as its Seawolf forebear, a signal that times are changing on the high seas.

Capt. Dave McCall admits to one vice. "I like to drive fast," he says, "I like to drive very fast."

The Navy has indulged McCall's need for speed by giving him command of its fastest attack submarine ever, the USS Seawolf.

On the record, Seawolf's top speed exceeds 25 knots. Some say the boat is so fast McCall could earn speeding tickets at sea. But he'd have to be found first. Besides being fast, Seawolf-class submarines, of which Seawolf SSN-21 is the first of three, are the stealthiest vessels in the Navy's fleet. "At 25 knots, our boat is quieter than the last Los Angeles-class submarines sitting at the pier," says Lt. Cmdr. Bob Aronson, the boat's executive officer.

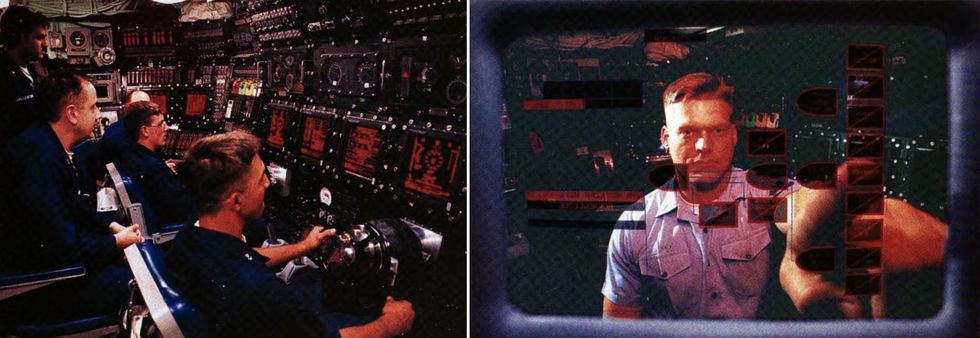

Popular Mechanics was invited to go for a spin in Seawolf during pre-operational testing off Florida's coast. The ride quickly turns into an adventure when we reach open water and McCall asks me, "Do you want to drive?" I'm recalling old submarine movies as I settle into the lightly padded driver's seat and wrap my hands around the wheel's black vinyl grip. After a quick rundown of the instruments, helmsman Billy J. Shirley orders “5 degree left rudder" to bring us to a new heading of 117.

I plant my feet squarely on the linoleum deck tiles and begin the turn. To my surprise, the helm answers with as much back pressure as the steering wheel on my Subaru. As the rudder indicator confirms my maneuver, I detect a slight sway. The digital compass shows the boat—which weighs 9,150 tons submerged—is halfway toward its new heading. I can't believe I'm inside a 52,000-hp submarine, plowing furrows in the Atlantic.

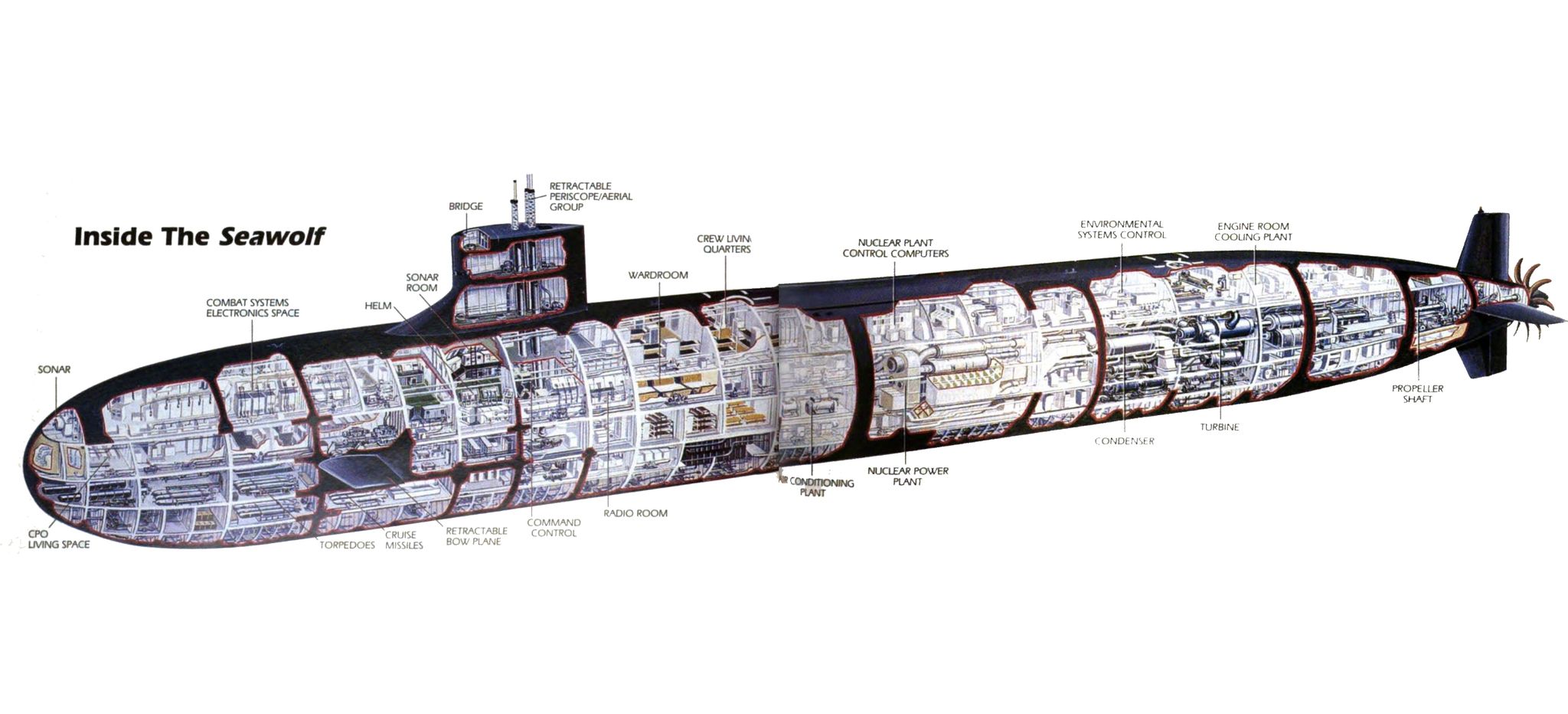

Seawolf is not only agile but larger than her dimensions suggest. At 353 feet, she is only slightly longer than her two immediate predecessors, the early nuclear submarine Seawolf SSN 575 and World War II-era Seawolf SS-197. These older versions have 27-foot-diameter hulls, but the Seawolf sports a 40-foot beam. Seawolf-class boats also have 7 feet more beam than Los Angeles-class boats. The resulting cigar-versus-cigarette geometry has enabled Electric Boat Corp. to employ the naval equivalent of Detroit's cab-forward design.

The aft two-thirds of Seawolf houses her General Electric S6W pressurized-water nuclear reactor, condensers, a pair of steam turbines and a secondary electric motor. Living and work space is located toward the bow. The command and control center—Seawolf's nerve center—has the feel of, and about as much headroom as, a basement recreation room.

As on all submarines, living quarters are tighter than on surface vessels. But on Seawolf they are hardly claustrophobic. Enlisted men's berthing areas sleep 40 in four-high racks separated by an aisle as wide as you'll find on a train. Officers bunk three to a stateroom, a little larger than a walk-in closet. “Next to the captain's stateroom, this is as good as it gets," says Lt. Dan Doney, looking up from his laptop computer. The captain has a similar room, but he doesn't have to share.

When off duty, officers spend much of their time in the wardroom, where they also take their meals. It is dominated by a large table that gives everyone about as much leg and elbowroom as members of large families get when they dig into the Thanksgiving turkey.

The Wolf's Den, the enlisted crew's mess, is slightly larger than the wardroom and filled with smaller tables, arranged like a railroad dining car. A single galley connecting the two areas serves restaurant-quality food for the 130-man crew. What the Navy takes away in space it returns at mealtime. Chefs who serve aboard submarines often move on to the White House kitchen.

Because Seawolf is one of the Navy's most computerized ships, its sonar and weapons areas look more like a college computer lab than the set of Run Silent, Run Deep. The General Electric BSY2 combat data system fills the weapons control bays with racks that feed information to the boat's 44 multifunction display terminals. “I can do more from my stateroom than I could from the control room of my last submarine,” says McCall, who previously served on Los Angeles-class attack submarines.

At the moment, the torpedo room looks unusually spacious. When testing is complete, Seawolf will be armed with an array of weapons, including 52 Mark 48 ADCAP torpedoes, Harpoon anti-ship missiles, and Tomahawk cruise missiles, mines, and decoys.

Although almost everything about the Seawolf is state of the art, there is one thing that even the crew of the original Seawolf SS-28—a 150-foot x 16-foot-diameter boat that was lost on the shoals of Santa Margarita Island, California, in 1920—would find familiar: the ritual and routine of the dive.

While I'm concentrating on keeping Seawolf on course, a quiet game of musical chairs begins around me. It's time to practice diving. Reluctantly, I surrender my seat to the seaman who will operate the Seawolf's retractable diving planes. For underwater operations, the helm shifts to the vacant chair to my right. As we approach the 1000-ft.-deep water where the exercise will be conducted, the dive officer takes the chair directly behind me.

"Submerge ship,” McCall orders.

"Dive! Dive! Dive!" a voice announces over the address system. Three distinctively shrill bursts of a klaxon follow.

"Dive! Dive! Dive!" the message repeats, as the klaxon sounds again.

"All vents open,” the officer of the deck orders.

From where I am standing, I see a 9-inch black-and-white television set. It is connected to a video recorder that captures the same images seen through the No. 2 periscope and was turned on once the dive began. It seems like I'm watching a scene from an old WWII movie.

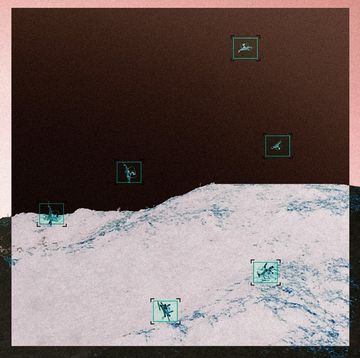

The low-slung deck of the Seawolf is rapidly awash. A bulbous wave before the bow collapses and is replaced by two ghostly lines that trace the shape of the now fully submerged hull. The periscope swings aft and focuses on the top of the rudder. In several seconds, it too disappears. A wave splashes against the periscope. There is a small trail of bubbles. We are underwater.

"Scope under,” the officer of the deck announces. Two minutes after the klaxon sounded, Seawolf has, to all intents and purposes, disappeared off the face of the Earth. I recall something McCall had told me earlier. "The submarine," he said, "is the original stealth weapon."

The dive and deck officers issue a stream of commands to trim and balance the boat. Seawolf begins to hover beneath the waves like a helium-filled balloon beneath the clouds.

There are two depth gauges in view of the dive officer. As we approach 200 feet, he leans out of his seat and turns a small valve that activates the deep dive gauge. The Navy says the Seawolf can operate at depths in excess of 800 ft. Jane's Fighting Ships puts the number at 2000 feet.

"Ahead full," McCall orders.

Seawolf's propeller bites into the water, pushing us deeper and deeper. I watch the gauge's needle pass the point at which crews in old war movies would erupt into a chorus of "Rock Of Ages.” None of that here just calm, very professional tension.

Nor, as the submarine rushes downward, is there the accompaniment of cracking and popping sounds from the hull. The Seawolf's modular hull functions as one piece of steel. It uniformly contracts.

Satisfied at his crew's performance, McCall orders the Seawolf to the surface. Several minutes later, assistant weapons officer Lt. Mark Perreault climbs up through the sail and cracks the hatch. I follow him up the narrow stainless steel ladder, scramble up on the wet, curved surface of the sail's very top, and enjoy the landless, shipless horizon.

When a sailor proves himself capable of being a submariner, the Navy honors his achievement by awarding him a distinctive insignia bearing leaping dolphins. As I look toward the bow, it appears Neptune has decided to bestow a similar honor on the Seawolf.

A pair of silver dolphins rises from the deep and swims alongside us as we make for port.