- A melted amalgam of nuclear fuel at Chernobyl is beginning to react.

- The issue is rainwater, which has activated materials buried deep within the closed plant.

- The reaction could burn out naturally, but it could also require human intervention.

On April 26, 1986, Reactor No. 4 exploded at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Ukraine, causing the worst nuclear accident in history. Now, thirty-five years later, smoldering nuclear “embers” are still buried within Chernobyl site, raising questions about just what might happen there—and what’s at stake.

➡ You think science is badass. So do we. Let’s nerd out over it together.

Ukrainian scientists recently realized that leftover nuclear fission fuel made of uranium has begun reacting again in an “inaccessible room” deep within a damaged area of the shuttered plant. The telltale sign is increased readings of neutron activity—a measurable byproduct of nuclear fission, according to the scientists from Institute for Safety Problems of Nuclear Power Plants (ISPNPP) in Kyiv, Ukraine, who held discussions about dismantling the reactor last month, according to Science magazine.

Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant is surrounded by a massive megastructure called Chernobyl New Safe Confinement (NSC). At NSC, there are hundreds of sensors working around the clock to monitor factors like air quality, and the sensors have detected increased neutron activity near the fallen reactor hall where the “embers” are.

Some zones within the NSC are fully sealed off in their own sarcophagus-like structure called the Shelter—including the reactor hall where scientists have noticed the increasing neutrons. That means tough questions about what the best course of action is.

Inside the reactor hall, everything is a dangerous mess. Science’s Richard Stone reports:

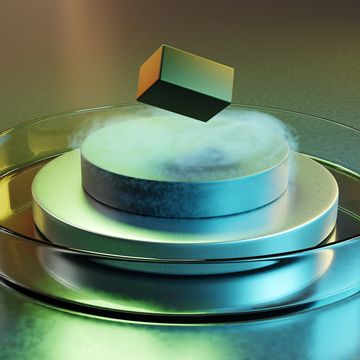

“When [the] reactor’s core melted down, uranium fuel rods, their zirconium cladding, graphite control rods, and sand dumped on the core to try to extinguish the fire melted together into a lava. It flowed into the reactor hall’s basement rooms and hardened into formations called fuel-containing materials (FCMs), which are laden with about 170 tons of irradiated uranium—95 [percent] of the original fuel.”

It’s important to note that experts don’t fear a second Chernobyl disaster, as there isn’t enough viable material or surrounding collateral for that kind of threat or damage. But the right kind of small nuclear activity could bring down the Shelter itself, which is 34 years old and “rickety.”

Scientists believe rainwater leakage has caused similar higher neutron readings in the past, and they’ve since installed special chemical sprinklers that can stanch neutrons in most of the interior of the Shelter. But some basement rooms are just out of reach even for the sprinklers.

One of the NSC’s great purposes is to finally, fully block out the rain. But water from before has still leached into the farthest reaches, where water helps to slow the neutrons and make them more likely to interact with the remaining nuclear fuel. Scientists figured the threat would decrease as the amount of water dried and receded, but somehow, the opposite has happened.

So, what are the next steps? The ISPNPP scientists say the growth in neutron activity is low enough that they still have a few years before they’ll need to act either way. In that time, they say, the incipient reaction could very well sputter out on its own—especially once the water supply fully dries out. Now that the NSC keeps the rain out, there isn’t any fresh water flowing in to continue to fuel new reactions.

But if the reaction doesn’t run itself out, the scientists are discussing their options. The location is far too poisoned with radiation for any human to venture in, but they might build a robot that can maneuver into the affected area to spray neutron-stanching chemicals, for example. Monitoring what continues to shift, disintegrate, and react within the Chernobyl complex remains a full-time job for some of the world’s greatest minds.

🎥 Now Watch This:

Caroline Delbert is a writer, avid reader, and contributing editor at Pop Mech. She's also an enthusiast of just about everything. Her favorite topics include nuclear energy, cosmology, math of everyday things, and the philosophy of it all.