This story was originally published in June 2018. It's been updated for the Disney Plus release of Hamilton on July 3, 2020.

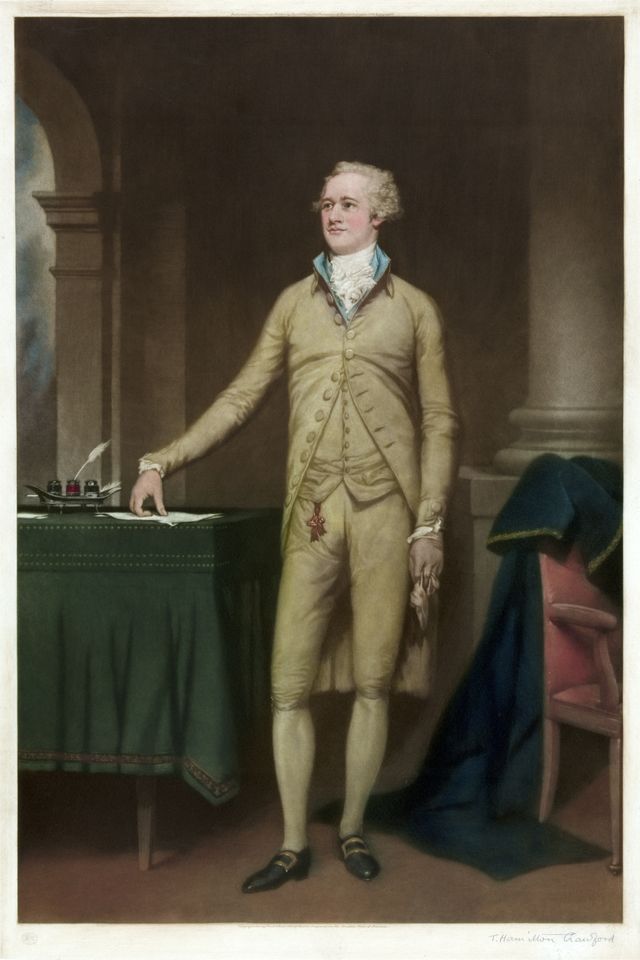

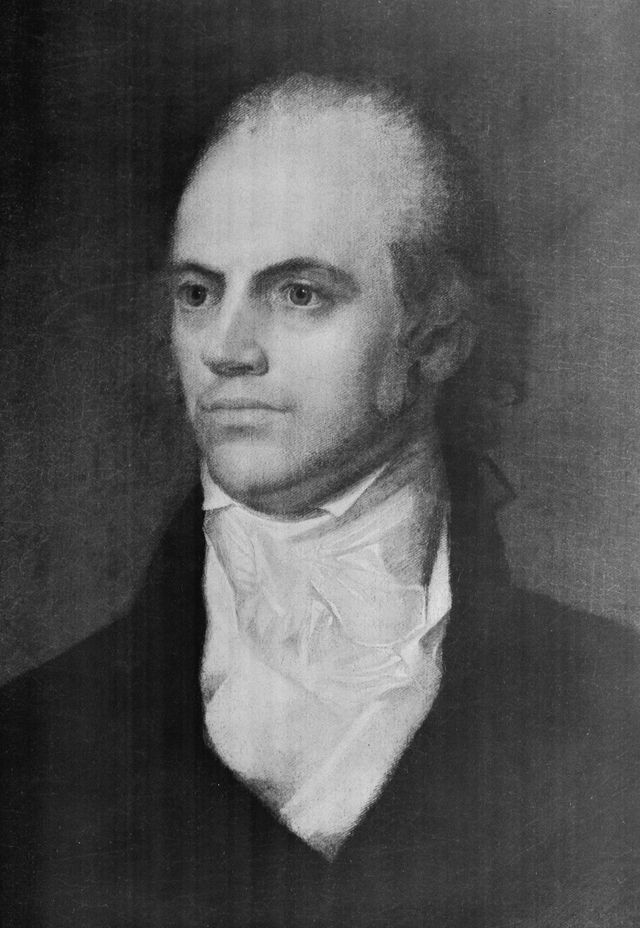

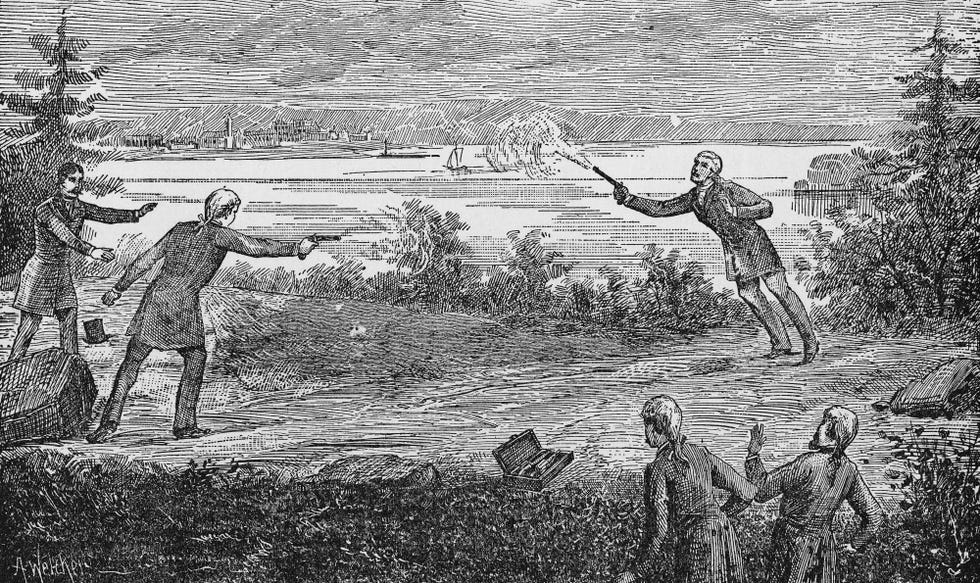

On July 11, 1804, on a New Jersey cliff overlooking the Hudson River, a duel between two controversial founding fathers killed revolutionary war hero and former Treasury secretary—Alexander Hamilton.

In the two centuries since, the duel has become an essential part of American lore. Accounts of what happened that day vary—witnesses say one bullet struck a tree, and the other found flesh. What we know for sure is that Vice President Aaron Burr remained upright while Hamilton fell, clutching a .54-caliber puncture wound to the abdomen. Thirty-six hours later, the “ten-dollar Founding Father” was gone.

The instrument of Hamilton's demise was an English-made Wogdon & Barton flintlock smoothbore dueling pistol. In 2018, 214 years after that fateful summer day, the walnut, brass, and gold pistols used by Hamilton and Burr were put on display at Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum in Washington D.C. It was a rare public appearance for the pistols.

“The Vice-President of the United States and the Secretary of the Treasury engaging in a duel... that’s something we could never imagine happening today,” says National Postal Museum chief curator Daniel Piazza, “At least, we would hope not.”

Many books have been written about this single duel and its repercussions. But even with a history well-documented, mysteries still remain about the pistols that killed a founding father.

The Tool of the Duel

During the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries, dueling was a popular—and fatal—way of settling disagreements among aristocratic men. Swordfighting was most popular (and less fatal) method during the early days of dueling, but the contest's emergence in America turned the pistol into the preferred tool of the duel.

Even with defined rules and etiquette, dueling was seen primarily as an American southern tradition. It’s unclear how many people fell victim to this archaic institution while attempting to defend one's honor or receive a woman's hand in marriage.

In the late 18th century, there was no one more associated with flintlock dueling pistols than Robert Wogdon. An English gunsmith with a shop on London's Haymarket Street, Wogdon made pistols that were world-renowned for being plain, practical, and balanced. The stocks were curved to cut weight, and the guns always came in pairs—to make sure each participant got one. Gun historian John Atkinson estimates the death toll of this particular brand of pistols at “many hundreds.”

In fact, Wogdon's pistols became so closely associated with dueling that in England the practice was sometimes referred to as a “Wogdon Case.”

In 1795, Wogdon partnered with another English gunsmith, John Barton, to ensure his pistols would remain in production after his retirement. Today, Wogdon & Barton pistols are highly collectible. They are represented in The Met’s collection as an example of artistic gunmaking.

Coming to America

While Wogdon earned renown for the standard dueling pistol, he also had a reputation for tricking out guns with custom features at the request of his aristocratic clientele. One such client was John Baker Church, Alexander Hamilton's brother-in-law and husband of Angelica Schuyler.

Historians believe that in 1797, Church returned to the U.S. with a pair of customized Wogdon & Barton flintlock dueling pistols that would become the weapons of the legendary duel. According to Nancy Palley, JP Morgan Chase vice president and archivist, he probably had the weapons made several years prior.

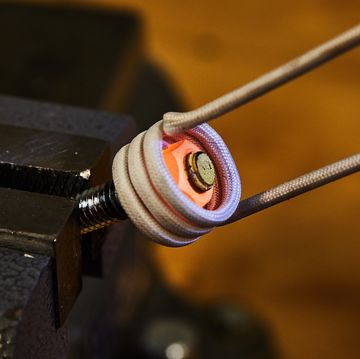

Because of this custom work, the pistols possess several features not often found on other Wogdon & Barton creations. Heavy, bronze fore ends were added to give the muzzle extra weight, which supposedly makes the arm steadier and aim more true. Both pistols have front and rear sights, rather than the more common aiming bead.

The most notable difference is the .54-caliber barrel, not the standard .50, meaning that the pistols needed a larger lead ball. Bad news for anyone caught in its path.

The most controversial feature of these pistols is the much-discussed "hair trigger" or "set trigger." This feature allowed for much lighter trigger pressure to fire a shot as opposed to ten to twelve pounds needed without the hair trigger. The mechanism was often hidden inside. To activate it, the trigger only needed a slight nudge forward. Using it also resulted in less pistol pull and a more accurate shot.

In 1974, when the pistols were disassembled for study and to create replicas in honor of 1976’s bicentennial, the supposedly “startling discovery” of the hair trigger grew into a the idea that Hamilton actually had a secret advantage. But other experts dismissed the idea as insignificant. “It wasn’t really new [information] to anyone who knew about these particular [types of] pistols," Palley says. "Hair triggers were not all that uncommon...at that time.”

Even on his deathbed, Hamilton reportedly admitted to not setting the hair trigger, providing compelling evidence that the former Treasury secretary didn't have any deadly intentions that July day.

"Hamilton never intended to shoot [Burr]," Palley says. "If he had set the hair trigger, we would have probably gotten off a better shot.”

The Duel In Decline

Over the years, other pistols have been claimed as the offending weapons. According to Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow, whose book became the inspiration for the musical Hamilton, these particular guns on display at the Smithsonian hold the “best claim to authenticity” thanks to the letters, documents, and chain of provenance associated with them. We can say with near-certainty that these were the weapons in the hands of those two prominent Americans more than two centuries ago.

But even though it's the single most important exchange of fire in American history, experts still don’t know who used what pistol. It's likely we never will.

After the duel, the pistols were returned to Church and subsequently passed down through the family—never to be fired again. During the Civil War era, one of the pistol’s flintlocks was switched out for a cap lock in an effort to modernize them. Then in 1930, the Bank of The Manhattan Company—originally founded by Burr in 1799 with Hamilton's initial support—purchased the pistols from Church’s great-granddaughter Mary Helen Church Gilpin. The Manhattan Company, now called JP Morgan Chase & Co., headquarters have been the pistols’ permanent home for the past 88 years.

The practice of dueling declined as the country roared towards the Civil War. After the war, the tradition vanished, likely because the country had experienced enough bloodshed. Today dueling is an archaic practice consigned to history, but these two pistols still preserve a legacy that shaped a nation with one pull of the trigger.

Matt is a history, science, and travel writer who is always searching for the mysterious and hidden. He's written for Smithsonian Magazine, Washingtonian, Atlas Obscura, and Arlington Magazine. He calls Washington D.C. home and probably tells way too many cat jokes.